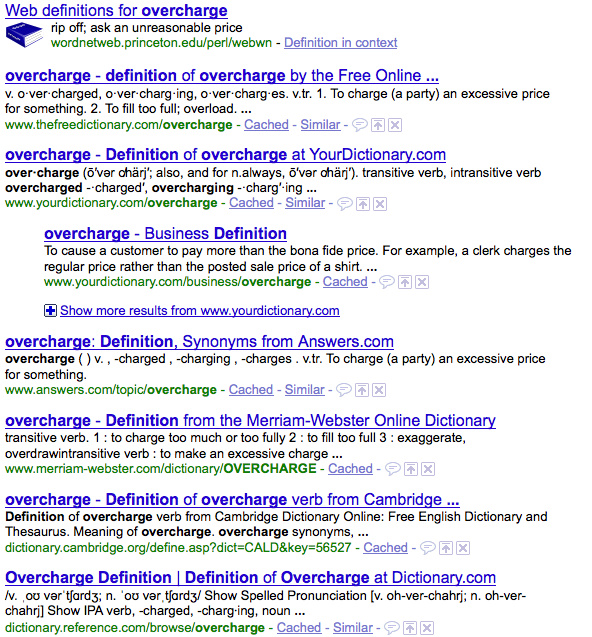

I wanted to know whether to say "overcharge customers" or "overcharge for customers" so I turned to our everlasting frienemy Google. As a good adviser, it encouraged me to add the word definition so that queries from online dictionaries would come on top. They did–with a vengeance. The following snapshot shows why Google can be our enemy at times. Too much.

I caused a mild panic. There are eighteen too many answers. I should have picked one easily, since they are all supposed to be authority – but I couldn't. Instead of choosing one, I turned to a distraction to calm myself down (= writing this blog entry).

This is exactly the situation depicted in The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less by Barry Schwartz. It is a brilliant read, which still can be summarized in a sentence: we don't feel happier by having more options to choose.

I decided to pick one dictionary that was supposed to be the best, or one of the bests, and stick with it. I selected dictionary.com, hoping such a great website name be run by guys doing an excellent job, or bought by such people. Pick up the best and stick with it – many people would do that too. The aforementioned book says:

Perhaps that's the reason consumers tend to return to the products they usually buy, not even noticing 75% of the items competing for their attention and their dollars.

…which leads to the "winner takes it all" syndrome created by our avoidance of facing the consequence of missed opportunities. In my case, I spent a considerable amount of time (a few minutes) and picked the best, not only because I wanted a good dictionary but also I didn't want to spend time thinking about missed opportunities. From a Wikipedia entry summarizing the book:

Missed Opportunities. Schwartz finds that when people are faced with having to choose one option out of many desirable choices, they will begin to consider hypothetical trade-offs. Their options are evaluated in terms of missed opportunities instead of the opportunity's potential. Schwartz maintains that one of the downsides of making trade-offs is it alters how we feel about the decisions we face; afterwards, it affects the level of satisfaction we experience from our decision.

There were times we innocently believed that more options will not only make us happier but also provides opportunities for everybody. We know better now – more options certainly improves the quality of the given service, because everybody is dying to grab users' attention. But they do not necessarily lead to our increased happiness or distributed opportunities. Winner takes it all, and even though we lament the increasing brutal society we live in, we are choosing so through our actions.

Appendix: the word "overcharge" does not need objectives. Thus I should say "the customers are overcharged."